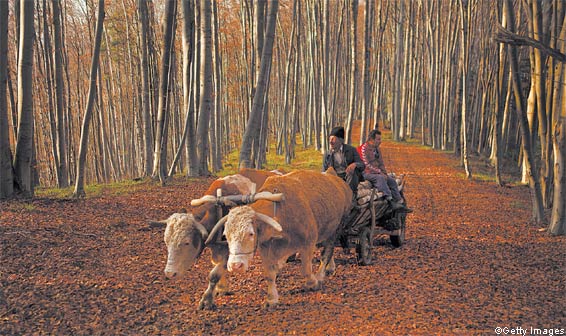

"Pierdut în Transilvania" - aşa şi-a intitulat jurnalistul Clive Aslet editorialul publicat în Financial Times, după o călătorie prin ţara noastră. A văzut Valea Verde din judeţul Mureş, s-a plimbat prin Piaţa Sfatului din Braşov şi i-a cunoscut pe oamenii din comuna Zăbala, în Covasna. Şi a ajuns la o concluzie: Transilvania este o lume care pare să aibă mai mult în comun cu romanele lui Thomas Hardy decât cu Europa modernă.

Preluarea articolului "Lost in Transilvania" - aparut initial in Financial Times in 5/11/2011, articol ce poate face parte cu succes din orice campanie de promovare a Romaniei.

Preluarea articolului "Lost in Transilvania" - aparut initial in Financial Times in 5/11/2011, articol ce poate face parte cu succes din orice campanie de promovare a Romaniei.

And it is beautiful. Raise your eyes to the hills and you’ll see an openness that is barely credible to someone from a crowded, industrialised country. Look down and you’ll find a deliciously scented pasture that is a tangle of wildflowers and herbs. No habitation is visible beyond the huts where the gypsy shepherds live and milk their goats. A man forks hay on to a rum baba-shaped stack. Otherwise there’s nobody to be seen – hardly surprising when you discover the road in this valley is so bad that it’s touch and go whether you’ll get over the bridge.

In this arcadia you wake to the sound of cowbells. The breakfast honey comes from bees that know nothing about the varroa mite that afflicts their cousins in more intensively farmed landscapes. The grapes clustering by the wall of the wooden church are warm from the sun. Geese cackle among the vegetables growing in the yards of the village houses. You might have one of them for dinner. Food is local here. It has to be – the nearest supermarket is hours away.

The son of one of the co-founders of MFI, the once-ubiquitous British furniture retailer that ceased trading in 2008, Lister first came to Romania in the 1980s, buying product for the stores. That was during the Communist era, when the forests were managed to textbook standards, not least because the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu loved to hunt in them.

Since his fall, in 1989, the state forestry service has been in decline. Large areas of woodland have been returned to the families who originally owned them but now might live far away. As the price of timber rises, so does the temptation to clear-fell the trees and take the cash. While light regulation might be charming in a sulphur hut, it also allows illegal logging. Corruption is rife. There’s no middle class to get hot under the collar about nefarious activities. Little by little, the forest is being nibbled away. Lister is devoting his considerable energy to saving it.

Lister had already turned 40 before he discovered his purpose in life. The turning point came when his father, Noel, suffered a serious illness 10 years ago. “I realised that it was pointless trying to compete with him any more. I could never be a better businessman than him, so I decided to devote my life to something that I’m passionate about: conservation.”

Initially, he bought the 23,000 acre estate – now called “reserve” – of Alladale in the Scotland Highlands, with the intention of “rewilding” it by flooding peatbogs that had been drained and reintroducing the wildlife that would have been there in the heyday of the Caledonian Forest. The great Carpathian Forest, half of which lies in Romania, is the other side of the coin. The Highlands might have lost its biodiversity but Transylvania is teeming with it.

Last month, the documentary Wild Carpathia had its world premiere in Bucharest. Lister financed the project in order to show urban Romania the wonder that lies on its doorstep. “Which other western country has such a charming rural life?” he says. “If only Romania would follow the example of Costa Rica, where a third of the forests are now protected. The future lies in eco-tourism.”

That industry is just beginning to appear in a number of lodges and guest houses, not generally de luxe but comfortable enough and set in heavenly surroundings. Having arrived at Targu Mures airport (Wizz Air flies direct from several European cities), located in the middle of an empty savannah, I set out with Lister to sample a few of them.

From the airport we drive to the Valea Verde Retreat at Cund: a journey of 40 minutes if, in this land of few signposts, you don’t get lost. It is owned by Jonas Schäfer, a German whose idealistic parents sold their house in Hamburg to come and help after the fall of Ceausescu in 1989. He is typical of the outsiders who forsee what Romania will lose if it goes down the wrong path. Accommodation is in a variety of rustic apartments formed from converted farmhouses. Before breakfast we hear the gypsy shepherd wheeling the milk churn up to the goats that are kept on the hillside; when we walk that way later, taking care to avoid some ferocious sheepdogs, the air is soft with the scent of the herbs that grow in the pasture. In the barn, which has been converted into a restaurant, we eat eggs from the hens roaming outside with shavings of truffle from the surrounding woods.

Next is Zabola, a yellow-walled chateau in Zabala, owned by the Chowdhury family, who returned to reclaim their estate, which had been expropriated by the Ceausescu regime. The 16th-century chateau sits in 34 hectares of parkland at the foot of the Carpathians. Guests stay in a recently renovated 18th-century outbuilding; a hunting lodge in the forest can also be rented for self-catering. Much of the food is from the two-acre kitchen garden. At dinner the dumb waiter rises, with theatrical effect, through the floor of the dining room, from the kitchen below.

Crocuses bloom in the fields along the bumpy road that leads to the tiny village of Zalanpatak. The charming guesthouse here is owned by Prince Charles, who through several charities works to conserve traditional buildings in the area. It has five bedrooms and a large wooden verandah overlooking the surrounding meadows.

I am tempted to say you might want to come and see this world before it disappears, but Lister believes that is defeatist. Visitors, he believes, will create a market for the felt slippers, home-made preserves and slipware pottery, perhaps helping the area to survive – along with the wolves and bears that live in the Carpathian forest.

Trophy hunters still go after the bears but other attitudes are beginning to prevail. Near Equus Silvania, a centre for riding in the wild Carpathian foothills west of Brasov, I spend an evening in a shaky wooden hide watching some of these fascinating animals. The shooting licence for this area has been bought by a local businessman who prefers to study bears, rather than kill them.

As dusk falls the bears sinuously slope up to food that has been left for them – the cubs gambolling, the mothers on the qui vive. You would not want to get between a mother and her cubs; the power of these animals is illustrated by the hide’s floor, part of which has been ripped away by a bear looking for food.

Equus Silvania is run by Christoph Promberger, a wolf biologist, and his wife, Barbara, a specialist in lynx. Both are campaigners for the forest and they arrange a helicopter to show me the extent of it. It is a warm day but rain is soon flecking the bubble of the machine as we swing towards the Piatra Craiului ridge. Roastingly hot in the summer but also damp, the conditions are ideal for trees. Below us, the hillsides are covered in a seemingly endless bristling mat of green pines, interspersed with the softer beech. There are few roads here and no sign of a dwelling, except for the occasional shepherd’s hut. Then into the headphones comes Barbara’s voice, pointing out an area – as bare as a badly shaved chin – where the trees have been felled.

Part of the problem is that forestry has little perceived value; according to Erika Stanciu, head of forestry for the Danube Carpathian programme at the World Wildlife Fund, it isn’t worth enough in exports for the government to make it a priority.

Over a plate of goulash on a terrace beside the charming Piata Sfatului square in Brasov, Lister unfolds two strategies for saving the forests. One solution is to unlock the carbon credits granted to countries such as Romania under the Kyoto Protocol, intended as a financial reward for not creating emissions that would otherwise have occurred. The other is rural development, a major plank of which must be tourism.

Little tourist infrastructure exists in rural Transylvania but that is part of its essence. You might not quite be in the position of Adam and Eve seeing a newly created world but you will certainly find it easy to be alone. At Equus Silvania I have breakfast with a woman from Switzerland, a country with grand mountains of its own, but who comes here to ride for a week or two at a time. She tells me, “Switzerland is like a garden compared to this.”

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu